I was recently reminded of the golden age of megastructure stories. As this is not yet commonly accepted genre shorthand, perhaps a definition is in order.

Megastructures are not necessarily simple. In fact, most of them have rather sophisticated infrastructure working away off-stage preventing the story from being a Giant Agglomeration of Useless Scrap story. What they definitely are is large. To be a megastructure, the object needs to be world-sized, at least the volume of a moon and preferably much larger. Megastructures are also artificial. Some…well, one that I can think of but probably there are others…skirt the issue by being living artifacts but even there, they exist because some being took steps to bring them into existence.

There may be another characteristic megastructures need to have to be considered a classic megastructure: absent creators and a consequently mysterious purpose. At the very least, by the time the story begins, the megastructure has been around for a long time.1 If there’s an example of a story about the construction of a megastructure, I cannot think of it. Have fun pointing out the well-known books I have forgotten in comments!

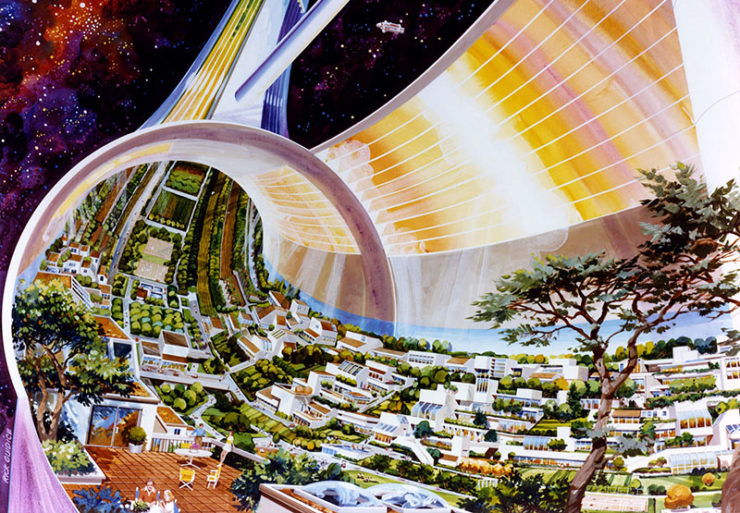

While there were precursors, the ur-megastructure, the one that largely defined how authors approach megastructure-stories, was Larry Niven’s 1970 Ringworld. In it, Louis Wu and a collection of allies travel to a strange artifact 200 light years from the Solar System2, a solid ring about 2 AU in diameter, clearly artificial and with a habitable surface dwarfing the surface of the Earth. No sooner does the expedition arrive than they are shipwrecked, forced to explore the Ringworld in person.

The general shape of the Ringworld ur-plot shows up in megastructure story after megastructure story. A mysterious object of immense size! An expedition, hastily dispatched to investigate! Survivors marooned! A dire need for sturdy hiking boots! And occasionally, Answers!

Niven very considerately followed his novel with a 1974 essay called “Bigger Than Worlds” (included in the collection A Hole in Space.). It’s a fairly comprehensive listing of all varieties of Bigger Than Worlds artifacts. About the only variant he seems to have missed was what Iain M. Banks later called an Orbital, the Ringworld’s smaller (but far more stable) cousin. I am not saying a lot of the authors who wrote megastructure novels after 1974 necessarily cribbed from Niven’s essay, just that I would not be surprised to find in their libraries well-thumbed copies of A Hole in Space.

Ringworld was followed by Clarke’s 1973 Rendezvous With Rama. Rama fell short on size but compensated with enigma. The Phobos-size artifact’s path through the Solar System allows the human explorers too little time to figure out what questions to ask, much less find the answers. None of their questions would ever be answered, obviously, as the very idea of a Rama sequel is nonsensical (as nonsensical as a Highlander sequel). Always leave the customer wanting more, not glutted on excess.

Bob Shaw’s 1974 Orbitsville featured a Dyson Sphere laid in deep space as a honey trap for unwary explorers. My review is here, but the short version is “Bob Shaw was a rather morose fellow and his take on why someone would go to the trouble of building a Dyson Sphere is appropriately gloomy. Be happy, at least, this isn’t John Brunner’s take on Dyson Spheres. Or, God help us all, Mark Geston’s.”

Fred Pohl and Jack Williamson’s 1973 Doomship begat 1975’s Farthest Star. They did Shaw one better: Cuckoo isn’t just a Dyson sphere. It’s a huge intergalactic spaceship. Pohl and Williamson were also the first authors, to my knowledge, to solve the gravity issue (that the forces within a shell cancel out, so there’s no net attraction between an object on the inner surface of a shell to the shell, only to whatever object—a star, say—is within the shell.) by putting an ecosystem on the surface of the vast ship. It’s a fascinating setting poorly served by the story Pohl and Williamson chose to set on it.3

Tony Rothman’s 1978 The World is Round is set so far in the future that the explorers are humanoid aliens. It otherwise dutifully embraces the standard features of the megastructure sub-genre: explorers become aware of an artifact the size of a small gas giant, which they race to explore in the hope of enriching themselves. As so often is the case, the explorers who manage to survive the initial stages of the adventure end up doing rather a lot of walking. There is, at least, a functioning subway. There is an absence of proper documentation that would be shocking were it not a defining feature of the megastructure genre.4

John Varley’s 1979 Titan featured a comparatively small megastructure, merely the size of a respectable moon. Again, the explorers end up marooned pretty much as soon as they reach Gaea but Varley managed to ring some changes on the standard themes of the genre. The first is that Gaea is a living being, artificial but alive. The second is that it is intelligent, able to answer questions when it feels like it. Sadly, Gaea is as mad as sack of weasels so the answers are not always helpful.

There is a steady trickle of later examples—Kapp’s 1982 Search for the Sun!, James White’s 1988 Federation World, Banks’ Orbitals and Shellworlds, Baxter’s Ring, Barton and Capobianco’s White Light, Niven and Benford’s Shipworld novels, and of course Charles Stross’ 2006 Missile Gap, which is without question the finest Locus Award-winning story inspired by a post of mine on a USENET newsgroup5—but the heyday of the megastructure seems to be over. In part this may be because the current zeitgeist does not favour stories set on what are effectively massive infrastructure projects.6 Mostly I think it is because the stock plot for megastructurestories is rather restrictive and authors have other chimes they want to ring.

One detail about megastructures that has puzzled me for some time is the incredible lack of women writing them. There’s nothing intrinsic to the concept that shouts “dude!” to me and yet, for some reason I’ve either never encountered a megastructure book by a woman or I managed to forget its existence. If you know of any examples, please do point them out to me in comments.

Originally published in January 2018.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is currently a finalist for the 2020 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]This is me weasel-wording because I am not sure if Brian M. Stableford’s Tartarus qualifies as a megastructure or not. In it, humanity has wrapped the entire Earth in an artificial shell. By the time the story begins, the shell has been in place long enough for the organisms left on the former surface to have been subjected to dramatic natural selection. I am also not sure if Fritz Leiber’s The Wanderer counts and if not, why not. Or rather, I am convinced it does not but I don’t seem to have a coherent argument for that position.

[2]Assuming the Ringworld and the Solar System have an average net relative velocity wrt each other for objects in our part of the Milky Way, the Ringworld (which is populated by the descendants of the Pak) could have begun its existence adjacent to the Solar System (also settled by the descendants of the Pak). I assume that’s a coincidence but it’s a suggestive one.

[3]Something I was reminded of while watching the third, most famous movie version of The Maltese Falcon: the works to remake in one’s own image aren’t the classics but the almost-classics, the works whose central conceit was much better than the final product. Singular, perfect works are hard to improve on but there are lots of books and films sabotaged by their creator’s shortcomings and the commercial realities of the day. If anyone wants an essay on “books I wish someone would use as a springboard for executions that are actually good”, just ask.

[4]Not that anyone would actually RTFM if one existed.

[5]I was inspired in one measure by Fred Hoyle’s October the First is Too Late, in one measure by “Bigger Than Worlds” and in one final measure by my friend John McMullen’s home brew role-playing campaign. Nobody works in a vacuum, at least not longer than it takes them to die of lack of air.

[6]I am not crying uncontrollably because the sound of Waterloo Region Light Rail construction has ruined my sleep since August 2014 and nobody can say for sure if Bombardier will ever deliver the trains. You are crying uncontrollably because the sound of Waterloo Region Light Rail project has ruined my sleep since August 2014 and nobody can say for sure if Bombardier will ever deliver the trains.

Linda Nagata’s “Memory” is a very excellent BDO novel.

One detail about BDOs that has puzzled me for some time is the incredible lack of women writing them. There’s nothing intrinsic to the concept that shouts “dude!” to me and yet, for some reason I’ve either never encountered a BDO book by a woman or I managed to forget its existence.

Maybe just a timing issue? The heyday of the BDO story, as you point out, was the 70s, and there were fewer women writing SF back then. And even in the1970s, most male authors weren’t writing BDO stories.

Some more:

Eon and Eternity by Greg Bear feature a very long artifact… I won’t say more to avoid spoilers.

Deception Well and Silver by Linda Nagata (and the in-between books Edges and Memory)

The Queendom of Sol books by Wil McCarthy might not qualify — the objects aren’t dumb — they’re smart matter — and their origins are known.

Did i miss an instance of bdo or are people reposting old comments?

@@.-@: People have apparently been posting comments to this article since (dramatic musical sting) before the article was posted! Also, now it’s about Megastructures instead of Big Dumb Objects?

Ah! That makes sense. This got reposted last week and my desire to remove infelicitous phrasing got it pulled for a week.

Pratchett’s first iteration of a discworld in Strata, which might be unique in being a megastructure novel in all respects (long treks included) except that why it was built is explicitly explained to both the reader and the main characters.

The chief alien bad guys in the Bobiverse series are despoiling local star systems to get raw materials for the Dyson Sphere they are building. And also for sources of protein, which makes no sense, but never mind

There was a DAW book I think I remember about a version of the solar system which was a giant disk with gaps for the planetary orbits. Was it artificial? Does this novel actually exist?

I hadn’t thought of Mark Geston for years. Admittedly the nation-carrying spacecraft in Lords of the Starship was barely a pinnace for a true megastructure, but it’s hard to beat that climactic engine test for “gloomy.”

@8 Well, if you’re going to despoil an entire star system you might as well use the whole thing. Even the meaty bits. Waste not want not.

David Weber’s Dahak (1991) is merely moon sized; would it count?

If webcomics count, the Buuthandi of Schlock Mercenary are a huge example. I love the understatement of the aeon: the word is an abbreviation for a phrase meaning “this was expensive to build”

Story about the construction of a megastructure: Rogue One.

Storybout the deconstruction of a megastructure: A New Hope.

The titular Halo in the Halo games should also count.

Ian Douglas has been playing with megastructures in both his Star Carrier and Andromedan Dark series; in which various high Kardashev number civilizations build everything from Tipler machines to every kind of megastructure in Bigger Than Worlds and then some more. The machines that protrude *between* universes in the later Star Carrier books must be candidates for the largest structures in SF…

@NancyLebowitz 9. I suspect you are thinking of Colin Kapp’s Cageworld series.

Do you count a Bank’s oribital as a megastructure? New plates are being landscaped in Player of Games.

Does James White’s Sector General count as a megastructure?

“4: Not that anyone would actually RTFM if one existed.”

I’m thinking if Chilton’s were to publish another SF novel like they initially published Dune, then a story in which someone does RTFM would be a great selling point for them.

Hmm..

“I must not guess. Guessing is the mind-killer. Guessing is the short-cut that brings total obliteration. I will RTFM. I will permit it to enter my brain and stay there. And when I am done, I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the manual has taken root, there will be no guesses. Only I will know which button to push.”

90s anime Sol Bianca: The Legacy has a sort of small Dyson Shell built around Earth (with the moon embedded in it, half in half out).

A bit more recently, the anime Valvrave The Liberator is set in and around an under-construction Dyson sphere (around an artificial sun). Seen here in the background, they’re building it by creating hexagonal, country-sized habitat-domes then linking them together.

Re: women writing about said megastructures; Elizabeth Bear’s “Ancestral Night” (2019) features a duel atop/amid the plates of a Dyson sphere, as well as a treasure hunt for another hidden Big Dumb Object. The sequel, “Machine,” is coming this October, with hopefully more explorations of all of these things.

I think one of the reasons why the megastructure genre seems to focus on treks across abandoned or decrepit ones is that, simply, a megastructure inhabited by a civilization that build and/or understands it would be an entirely different novel — when you have a working Kardashev Type II or Type III civilization, then the plot has to be about them and what they’re doing, because they have overpoweringly so much more ability and agency than human-scale beings.

Zindell’s Neverness et sequelae has giant matrioshkya brains in the background, but we mostly see the ruined remnants, because a mind operating on that scale would be very difficult either for authors to write about or for readers to understand the internal thought processes of.

The Cageworld (Colin Kapp) series is clearly about megastructures being built – in the end around several stars. The purpose is the ever growing population of the human race.

The rewrite has rather invalidated the end of the first footnote. The Wanderer is clearly a megastructure, however I agree with the original assertion that it is not a BDO. Mostly because there are plenty of people aboard who seem to know how to make it work.

I think that the story of the Earth Space Elevator in Arthur C. Clarke’s “Fountains of Paradise” could be one of the construction of a Megastructure…

In Julian May’s Galactic Milieu series, intergalactic business is carried out on Concilium Orb, an artificial world (Julian was female).

Robert Reed’s book Marrow and its sequels should not be left out, nor should the fractal habitats of the retired species from Brin’s Uplift series.

Re sequels to Rama, I see what you did there.

” If anyone wants an essay on “books I wish someone would use as a springboard for executions that are actually good”, just ask.”

<raises hand>

Fascinating :)

Ann Leckie’s trilogy starting with Ancillary Justice has a Dyson sphere in the background as the center of an interstellar empire, but the stories are not set there or particularly interested in it.

Alastair Reynolds’ House of Suns has plenty of megastructures in its setting, but they’re just background, not the focus.

Roger MacBride Allan’s (tragically incomplete) series beginning with The Ring of Charon has, as I recall, at least one incomplete Dyson sphere, although that may be more of a case of deconstruction rather than construction.

How about the gatespace in The Expanse?

@19 Does that spaceship bridge have parquet flooring?

21.

“when you have a working Kardashev Type II or Type III civilization, then the plot has to be about them and what they’re doing, because they have overpoweringly so much more ability and agency than human-scale beings.”

I don’t think so. People have overwhelmingly more power than mice, but you could have fiction by, for, and about mice in a human-dominated world.

If James hasn’t already done a “living in the interstices” series, it would be a worthy topic.Tenn-s Of Men and Monsters, for example.

@32 It does indeed.

One of the things I love about SF anime is that it tends to have such flamboyant designs compared to American sci-fi TV, where everything is brushed metal and monochrome pastels.

How about the Final Encyclopedia? Gordon Dickson’s creation, is it big enough to qualify as a megastructure?

Manhattan alone is about the length of Phobos, so why not Cities in Flight?

the host of megastructures in the Culture series.

The Starfarer series, by Vonda McIntyre, from the ship they are flying to the ones they encounter are megastructures. The plot and characterization in those couldn’t be more unique. What wonderful reads!

The Doctor Who novel The Also People is set within a Dyson Sphere, inhabited by The People, who built it. It’s the Doctor meets the Culture meets a murder mystery.

Some of the later Uplift novels at least saw a Dyson Sphere or some fractal variant; I don’t recall if they went inside.

Honorary mention to Douglas Adams and Magrathea; according to that, we’re all living on a megastructure right now!

Which reminds me of a construction novel: Building Harlequin’s Moon, by Brenda Cooper and maybe Larry Niven.

(I expect debate about how building a planet somehow doesn’t qualify as a megastructure.)

the books by James SA Comey (the Expanse series) include construction of a megastructure. At least one of James White’s novels contains a living planet (confusing everyone until they figure out it’s a being).

I’m surprised you didn’t mention Philip Jose Farmer (Riverworld, The World of Tiers, etc) or Jack Chalker with the Well of Souls books.

@40, Major Operation is the book. Not only is the planet alive, it needs medical help. White once said, ‘Whennever I create a new species it immediately falls ill and has to go to Sector General’.

Major Operation was the first White I ever read!

Battleships as scaples!

@9 NancyLeibowitz

Countersolar by Richard Lupoff sounds like the one. I believe it was a sequel to Circumpolar where the Earth is flat.

Dr. Richard Seaton would like to have a word with you about the requirement that the megastructures be abandoned and of mysterious purpose. He has never abandoned the Skylark of Valeron and it’s purpose is quite clear: to blow the pojees out of anyone who is not humanoid and looks at him the wrong way…

No mention at all of the Orbitals in the Culture? They have thousands of them and most of them are big enough to house billions of people.

IIRC, Player of Games has discussion about the construction of an Orbital, but it’s tangential to the plot. Little bits are sprinkled through many of the books in the series.

While they don’t strictly focus on it, the new ‘Rise of the Jain’ trilogy by Neal Asher involves a Dyson Sphere construction project. It’s also mentioned/visited in some of his earlier Polity universe books as well.

Alastair Reynold’s Pushing Ice is another one, with two megastructures for your money (I’m counting Janus as one)

“The City” in the manga and anime Blame! by Tsutomu Nihei.

The Manga Blame! by Tsutomu Nihei takes place in an ancient mega structure of unknown size. It is inhabited by humans and post-humans and policed by silicon based life forms that sometimes get downloaded from the net sphere and wreak havoc. The structure itself is crumbling but also still being built by machines of titanic proportions. It’s unclear where the mega structure is located (*)if it’s on a planet or somewhere in space and it’s also unclear how and why it was built and what happened to cause it’s downfall and decay.

(*) Well, there’s a prequel story that hints that it started out as a city built on the moon.

Neal Stephenson’s “Seveneves” includes a mega-structure built around the Earth in the final act of the novel, which takes the reader on a journey from near-current times where the Moon falls apart, to building a space station to preserve the species along with gene modifying to create subspecies, and then on into the future concerning the ring megastructure and eventual “rediscovery” of the Earth’s surface.

Surprised to see that “Ker-plop,” by Ted Reynolds (first published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in 1979) was omitted.

Would Trantor from the Foundation series count?

Generation ships – Gene Wolfe’s Book of the Long Sun series.

That Valerian movie takes place on a megastructure, and the opening of the movie documents it’s ongoing creation. Warning, that intro, beautifully set to David Bowie’s Space Oddity, is the only part of the movie worth watching. If you watch the next scene you’ll immediately understand what I mean.

“If there’s a story about the construction of a megastructure I cannot think of it” Star Wars comes to mind…..

Would the Endymion rebel habitat count? Dan Simmons wrote that in the 80’s, sometime, I guess.

Grand Central Arena by Ryk Spoor qualifies. To quote the author’s description:

“The Arena is one of the largest constructs ever imagined by man: an entire universe enclosed and controlled, an artificial structure somewhere between 16 and 32 light-years in diameter, within which is contained a complete, detailed scale-model of our entire normal-space universe, with each star system represented by a Sphere, roughly 20,000 kilometers in diameter, which itself contains a scale replica of the individual solar system, with all bodies above a certain size represented.”

The adventure for Traveller 2300 “Bayern” features an expedition to the Pleades. When the humans get close enough they realize that the irregularities between the stars they’re detecting are due to some sort of multi-dimensional construction project. An attempt to contact the builders can at best result in a vision that is all merely one anchor point of an inexplicable project spanning the Galaxy. Well, that and a character might be flipped left for right in a molecular level…

What about Allen Steele’s Hex?

“If there’s a story about the construction of a megastructure I cannot think of it” Star Wars comes to mind…..

Arthur C Clarke, “The Fountains of Paradise”, comes close – though a space elevator is too small to count as a megastructure. Macrostructure?

Terry Pratchett, “Strata” is about planet building. (“END NUCLEAR TESTING NOW”.)

The trouble is that it’s more difficult to depict a civilisation that can build megastructures and still faces challenges that need to be overcome – and no challenges, no drama, no story.

A bit late posting here, but have to mention Karl Schroeder’s excellent Candesce series featuring planet-sized bubbles filled with atmosphere and zero gravity.

As far as i know the first mega structure described was in Olaf Stapledon’s novel, ‘Starmaker’ ( 1937) , where he invents the precursor to the dyson sphere.

Charlie Stross’ large discworld in “Missile Gap,” which could be a good starting point for a novel’s worth of short stories…

Ryn of Avonside is a fantasy story that takes place on a sci-fi ringworld, and it’s written by QuietValerie.

https://www.scribblehub.com/series/88122/ryn-of-avonside/

Megastructures are one of the most fascinating aspects of sci-fi literature. Especially the Dyson swarms, Dyson spheres, and orbital rings. If you like to see what they would look like, check out the video game called Stellaris which is hosting tens of various megastructure ideas.